HISTORY

GLOBE

Globe is a city steeped in Wild West history. Nestling close to the majestic peaks of the Pinal Mountains, and a 90 minute drive from Phoenix, the city can trace its origins back to the 12th century when the area was first settled by the Salado tribe of Native Americans. In those times it was known as Besh-Ba-Gowah, which translates to “the place of metal.” Little did its early occupants know just how relevant that name would be to the history of the area that would become modern-day Globe.

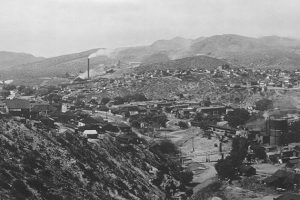

Rich deposits of silver were discovered in 1875 on the nearby San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation that lead to a mining camp being established in the location. Progress came quick as it did in many such boomtowns, and by 1876 Globe was on the way to being a fully incorporated settlement with stores, banks and other civic amenities. The inaugural edition of the town’s first newspaper, The Arizona Silver Belt, came off the press on May 2, 1878. Three years later, Globe became the Gila County seat, and soon after it got its own stagecoach route, connecting it with Silver City, New Mexico.

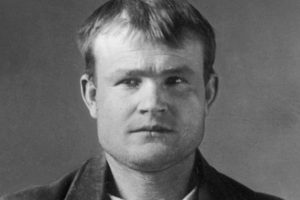

Despite its rising prosperity and influence, Globe remained a frontier town, with a colorful history of episodes that put it firmly on the map of the Wild West. Gunfights, stagecoach robberies, lynchings and Apache raids were all part of life in Globe during that era. It was in many respects, an outlaw town. Following the legendary Gunfight at the OK Corral in 1881, one of the surviving outlaw brothers, Phineas Clanton, made Globe his home. His grave can be seen in the old town cemetery. Rumors abound to this day that the most famous outlaw of all, Butch Cassidy, leader of the Wild Bunch, settled in Globe after surviving what was supposed to be a fatal shoot-out in Bolivia.

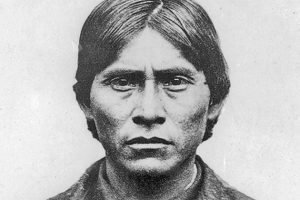

The neighboring Apaches posed a lingering threat, regularly conducting raiding parties among the mines and ranches outside of town. In 1889, the notorious renegade, the Apache Kid was imprisoned in Globe, and during his subsequent transportation to the territorial prison in Yuma made a bloody escape, killing two sheriffs. Known as the Kelvin Grade Massacre, the United States Army instigated a major manhunt in response, though the Apache Kid was never found.

- The Apache Kid

- The Arizona Silver Belt

- Butch Cassidy

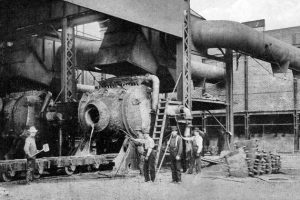

Established in 1880, the Old Dominion Mining Company built a copper mine to the north of the city. It was not the only copper mine in the area, though it was destined to become the most dominant and play a major role in the evolution of Globe and the surrounding area. With the arrival of the railroad in 1898, then known as the Gila Valley, Globe and Northern Railway, the mine had a far more economical means of getting its precious metal to the marketplace. Ownership of the mine subsequently passed to the copper giant Phelps-Dodge, who plowed significant investment into the venture.

During the early 1900s, the Old Dominion mine expanded and prospered, helped in no small part by the rising demand for copper brought about by the advent of World War I. The city of Globe benefited from this economic success, and the downtown became home to many fine buildings, including the aptly named Dominion Hotel on South Broad Street. However, discontent among the then unionized workforce was becoming an issue.

In the summer of 1917, a strike by the miners over wages and conditions resulted in an intervention by troops of the 17th Cavalry who were called in to restore order. Following a number of arrests and a lengthy period of negotiations, the strike was broken and the miners returned to work.

Production was suspended during the post-war Depression, and never really recovered. Persistent flooding and a decrease in the quality of ore rang the the death knell for the mine. Sadly, the Old Dominion closed down in 1930. Over its 50 year lifetime, the mine was the economic bedrock of Globe, creating both wealth and employment. In total, it yielded 800 million pounds of copper, and generated earnings of $134 million.

A decade later, the site came into use again, supplying water to both domestic and industrial users around Globe. It gained a second lease of life from the very element that had played such a role its demise, water.

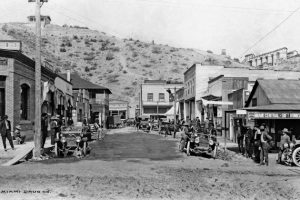

- Globe, 1907

- Miami

- Miami Mine

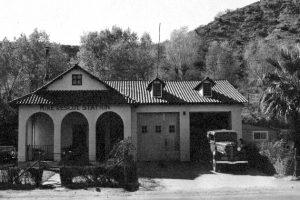

- Globe Mine Rescue Station

- Downtown Globe

- Old Dominion Mine Smelter

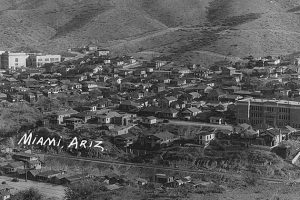

MIAMI

The story of Miami runs alongside that of Globe, both born from the same rich deposits of copper known as the Old Dominion system.

Before Miami appeared on any map of the territory, the area had already entered into Western folklore as the site of the infamous Bloody Tanks Massacre. Following a number of raids by Apaches around the Prescott area, a group of volunteeers led by King S. Woolsey decided to track down the culprits and retrieve the cattle and other items stolen.

Woolsey and his men pursued the rustlers deep into the wilds of the Tonto Basin, and in due course came upon a band of Pinal Apaches camped by the waters of a desert wash. While the encounter started amicably with a pow-wow, violence soon broke out, apparently triggered by Woolsey’s party. Twenty-four Apaches and one of the homesteaders met their deaths in the ensuing fight. From that day on, January 27, 1864, the area became known as the Bloody Tanks Wash, owing to the large amount of blood that spilled into and colored the waters of the stream. It would be next to this dramatic landmark that the town of Miami would rise.

Over the following years, several copper mines opened up in the vicinity, such as Keystone, Live Oak and Black Warrior, prompting a demand for local labor. Initially, the workforce traveled daily from neighboring Globe, but as the mines grew so did the need for a more convenient solution.

As the new century dawned, the labor requirements of two more major mining operations, the Inspiration Mining Company and the Miami Copper Company, added to this pressure. After a number of propositions failed to get off the drawing board, the town of Miami was finally established in 1909. Its creation was largely down to the efforts of one man, Cleve W. Van Dyke, an ambitious property speculator from Minnesota. However, the mining companies in the area also held great influence. Indeed, even the very naming of the new settlement proved to be a source of contention as Van Dyke wanted it to be known as Cordova, while the Miami Copper Company were determined it should be called Miami. For many years forth, the citizens of Miami would have their lives goverened by these two often competing interests. Not only did Van Dyke profit from the sale of land for the town, but he went on to own many of its early utility companies, as well as the prominent local newspaper The Arizona Silver Belt.

In 1909, the Gila Valley Railway reached Miami, greatly increasing the capacity of copper that could be brought to market.

- Downtown Miami

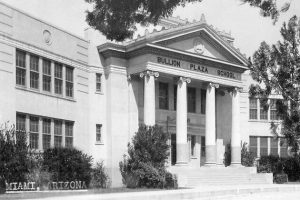

- Bullion Plaza School

- Miami Today

The 1920s brought about a period of rapid development, with the construction of schools, churches, lodges and theaters. Many of the streets that sprang up carried the names of prominent townsfolk such as Davis Canyon Rd, named after John Davis, the owner of the First and Last Chance Saloon, Latham Blvd, after the owner of a gents furnishing store, and Sullivan St, in honor of Pat R. Sullivan, an executive of the Silver Belt newspaper. By this time the population was 6,689. The area had always been geographically isolated, though with the completion of the Miami-Superior highway on April 29, 1922, the recently founded state capital of Phoenix with all its economic and social attractions became readily accessible.

During the years of the Great Depression, the population declined markedly, though with the advent of World War II and and surge in demand for copper, Miami once more became something of a boomtown. It continued to prosper during the subsequent decades, until one by one the major mines began to close, leaving only the Pinto Valley mine that still operates to this day and stands as a reminder of Miami’s claim to be The Copper Center of the World.